Today’s Wonder of the Day was inspired by clayton. clayton Wonders, “Who was the first poet?” Thanks for WONDERing with us, clayton!

Do you enjoy writing? Keep a journal of your thoughts? Maybe you write plays with your friends. If poetry is more your style, you might be like the subject of today’s Wonder—Paul Laurence Dunbar.

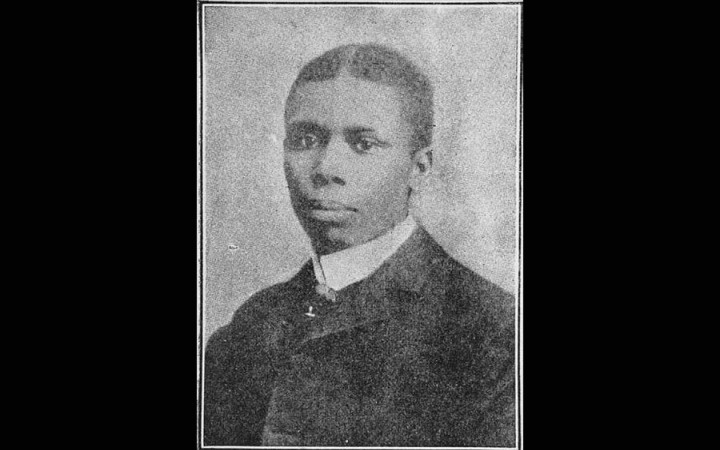

Many call Paul Laurence Dunbar the poet laureate of African Americans. He wrote novels, short stories, essays, news stories, and lyrics for operas and musicals. He was the first African-American man to be paid for writing poetry.

Dunbar’s parents, Joshua and Matilda, were born enslaved in Kentucky. Joshua escaped his enslavers and fled to Canada. He came back to the United States to fight in the Civil War. Matilda was freed and went to live with her mother in Dayton, Ohio. Joshua and Matilda met, married, and had two children. Paul Laurence Dunbar was born June 27, 1872, in Dayton. After only a few years, Dunbar’s parents divorced. Matilda raised Paul while doing laundry for the Wright family. Two of the Wright children, Orville and Wilbur, gained fame in the early 1900s as pioneers of aviation.

Matilda instilled a love of reading and poetry in Paul. During her enslavement, she did not receive formal education. As an adult, she took night classes to improve her literacy. She taught Paul to read before he entered school. He wrote his first poem at age six.

Paul attended Dayton’s public schools. He was the only Black student in Central High School. In high school he was class poet, a member of the debate group, and president of the school’s literary society. He also edited the school’s newspaper. With the support of classmate Orville Wright, Dunbar published and wrote a short-lived newspaper for the Black community, the “Dayton Tattler.”

Even though he was very smart and graduated from high school, Dunbar didn’t have the money to attend college. He hoped to study journalism or law. Because there were few jobs for Black men, he took a job as an elevator operator in a Dayton office building. This job gave Dunbar the time to write often.

He self-published his first poetry book, “Oak and Ivy.” He sold copies of his book to people who rode on the elevator with him. Dunbar wrote poetry in both standard English and in dialect. His dialect poetry became the most well-known.

As Dunbar started his writing career, several well-known people read his work and heard him speak. Poet James Whitcomb Riley and abolitionist Frederick Douglass supported Dunbar. With their help, Dunbar traveled and recited outside Ohio for the first time.

Dunbar wrote about the experience of African Americans during and after the Civil War. He wrote of their dreams and feelings. He also told of their hardships and racist treatment.

In 1897, the Library of Congress hired Dunbar as a researcher. He moved to Washington DC. While working there, he became increasingly more ill. He thought his coughing was because of the dust from the Library’s books.

Dunbar married fellow writer Alice Ruth Moore in 1898. Dunbar wrote to his future wife after reading her poetry in a magazine. They shared letters for two years before meeting and eloping.

Alice and Paul’s marriage only lasted four years. They broke up in 1902 but never divorced. His health was much worse by this time. Doctors found out he had tuberculosis. There was no medical cure. Dunbar began drinking heavily to combat his cough.

Dunbar and his mother, who had lived with him and Alice, traveled to New York and Colorado. Doctors thought this might help his health. Eventually, he bought a house for the two of them in Dayton. He died there on February 6, 1906. Matilda kept Paul’s rooms as he left them. The house is now a museum.

Though only 33 when he died, Dunbar left a legacy. Several Black poets of the Harlem Renaissance were inspired by Dunbar. Dunbar’s name is on schools across the United States to serve as motivation for what students can achieve.

Standards: CCRA.R.1, CCRA.R.2, CCRA.R.3, CCRA.R.7, CCRA.R.10, CCRA.L.1, CCRA.L.3, CCRA.L.4, CCRA.L.5, CCRA.L.6, CCRA.W.4, CCRA.W.5, CCRA.SL.6